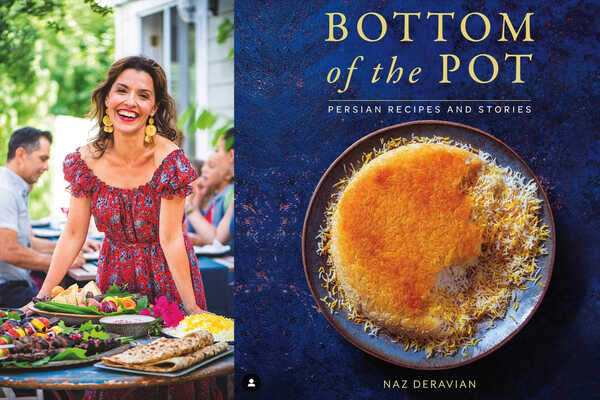

Growing Up Irooni- Melody Moezzi on The Rumi Prescription

Melody Moezzi is most recently author of the book The Rumi Prescription, in which she talks about how the poetry of Rumi became a lifeline for her, helping her to gain wisdom and insight in the face of a creative and spiritual roadblock with the help of her father, a lifelong fan of Rumi’s poetry. We covered so much in our Growing Up Irooni interview, from the controversy of Coleman Barks and why Melody is actually a big fan of his work, to learning Persian poetry in its original language, to becoming an artist in a culture that isn’t always the most hospitable to being an artist as a profession, to discussing mental health in a culture that isn’t always the most hospital to talking about mental health, and so much more.

Listen to the interview below, or scroll down for an edited transcript of our conversation.

Leyla Shams: Melody Moezzi, Thank you so much for talking with me today.

Melody: Thank you so much for having me. I'm so thrilled to be here.

L: Melody is the author of the Rumi Prescription.

M: It's going into its second printing in Iran.

L: Are the translations in the book all your own translations?

M: My dad helped me with the Persian, but ultimately the choices of words are mine.

L: I thought we could start with a reading of the passage. And then I'll ask you some questions about your upbringing and about the book.

M: Perfect. So this is from the author's notes of their own prescription and just a couple paragraphs that are separated.

"There's a reason Rumi's poetry has survived so long and reached so far. His rhymes honor the sublime power of meeting. Begging to be sung despite, and because of the fact that his verse is so explicit, that it stands alone even without music and in translation Rumi's words resonate across time and space.

Speaking to the unifying force within all of us that transcends language, culture, race, and religion here in rest. Rumi's notion of the beloved known by countless different names. God truth, light nature, beauty, and the universe to name just a few, but sharing a common essence, inextricably rooted in. As such the beloved is not a passion we ought to pursue, but a sacred, inherent tips that lives within each of us that connects us.

And that if we let it wakes us up."

I'll stop there.

L: Wonderful. And so the premise of the book is basically that you had this mental breakdown that happened in your life. And that, that you had grown up hearing your father recite Rumi poetry, and he's a very devoted, Rumi devotee

M: An addict.

L: I think a lot of Iranian dads, right? That's a common experience.

M: That's true. Exactly.

L: And that this occurrence in your life led you to go back to your father and actually express interest. And really learn these poems and study them fully. Is that a good summary?

M: That's a great summary.

Yeah, it took a long, like most kids, like I was a brat and I don't, maybe not like most kids, but it makes me feel better to say that but I was a brat. My dad was reciting all this poetry to me. With every lesson, there was a poem that came with it and I was always rolling my eyes being like stop because each time he would recite a poem.

He also had to translate it from classical Persian to normal Persian. And then from normal Persian, whatever words, I didn't know were translated to English, right? So it's just like a long process. And I was very not interested in it. And once I had my manic episode, which coincided with a mystical experience, that was when I really understood where Rumi was coming from.

He has a poem where he says in love with insanity, I'm fed up with wisdom in rationale. And I'll give you the Persian of it. It's āshegham man bar fa'né deevānegee, seeram az farhang ō farzānegee.

So that translation is not perfect because he says I'm in love with the profession sanity. So like the idea that like. I never related to that, but this idea that, for Rumi, there's two kinds of crazy and everybody's crazy. And you have a choice. You can be the crazy that's rooted in love, and that's what makes a mystic. Or you can be the crazy that's rooted in fear, and that's what makes a lunatic and a fundamentalist. And so this idea of being able to choose, I was very into choosing the version that was rooted in love and that mystical experience was part of it. But he also recognizes common sense as well.

And I am as well. So I knew that I had a clinical condition. In my case, I had bipolar disorder type one. I found out was through this manic episode and a psychotic break that included hallucinations and delusions. And it's the only time I ever in my life had delusions because finally, once I knew what it was, I could treat it.

Thank God both my parents are doctors, so they were very quick to say, this is a clinical medical condition. It needs treatment. We don't know what causes it. We don't have a blood test. We don't have an x-ray, but we know you have a clinical condition. I don't even drink alcohol, let alone do drugs, but somebody who's manic looks like somebody who is high on cocaine or methamphetamine. That was obviously the first thing they tested me for. But no, like this was just naturally hallucinations and delusions happening in my own brain. And so that ultimately led to me getting that bipolar diagnosis.

And once I knew what I had, I could treat. And it was important to me to accept it as a clinical condition, but also to accept the mystical part of that experience as being valid as well, because I had this moment of really feeling so connected to every living thing around me in a way I've never had before and not just connected, but knowing that God is within me and within all of those living.

And it was just like an extraordinary, amazing experience. I' ev never done psychedelics, but I've heard those kinds of psychedelic experiences. So I had this sort of revelation and I would never give that up. And I'm so grateful that I could have it without any drug, so there on my own, but also that's a very inconvenient place to be in our current reality.

So I needed that medication. I still take medication. I'm grateful for it, but I just wish the medical community had been more understanding of the mystical side of my experience and the spiritual side of it. And I wish that my Muslim community would have been a lot more understanding of the clinical side of it, because I did have some Muslim friends who were like, this is gin.

No, not right. And I think God, and I know a lot of people who have been taken, whether Muslim or Catholic or other faith, have been taken for exorcisms for this kind of stuff. So I was very lucky as that's a long way of saying I was blessed and lucky to have a family that understood this needed treatment.

L: And they had the scientific background too. And they were able to help you. It's amazing. I want to just say I loved the book. I really loved it. And there was just so much in there that I related with. You cover a lot in there from, growing up with an Iranian background and the whole Trump administration and everything that happened.

The reluctance of the Iranian community to talk about mental issues. I also grew up in the same house as my grandfather, and he was also a scientist who just loved poetry and at the end of his life, he retired early and he moved to Dallas suburbs, which was very depressing for him.

And the way he found salvation from that was that we got him a calligraphy pen and he started writing his favorite poems and near the end of his life, he wrote, I really related with what you were saying, like your dad just had has all these scribbles everywhere. I have all these scribbles from my grandfather.

I would tell him, oh look, there's a pretty bird outside. It looks like a little prince. And I remember he wrote me a poem about a prince and and that was the last thing that he wrote to me that I have framed on my desk. As he was writing them, I also was like, every week I'm going to call you and we can go over these poems together.

And it just never happened. I was in college. Parties going on, there were friends.

M: I was hoping by the time I finished writing the book, my first Persian would be pristine. Like I had to have very high hopes and now I'm just accepting that it's the way it is. My parents, like consistently are like, it's cute. Like I do events in Farsi and I mess up, like I say things wrong, but there was a recent event that I did- oh, I'm going to forget what the word for it. But my dad was talking about me in a very positive way, but I didn't know what it meant. And it just, the irony of it was so good. I didn't know what the word genius in Farsi was. But he was calling me a genius in Farsi. What does that word mean?

L: Okay. So that leads me to my next question. I want to go back to your upbringing and talk about where were you born and what, where did you grow up?

M: I grew up mostly in Dayton, Ohio. I was born in Chicago. I was born in 79. So the year of the revolution and my parents were though I was by birth in America and my parents were

Both born in Iran. So we were kicked out after the hostage crisis. Our there documents were no longer valid after the hostage crisis and we were kicked out and we went back to Iran. The Iran/ Iraq war was going on. It wasn't the best time to be there. And we ended up going to Greece and France and finally making it back to the U S and then Dayton.

We jus t wanted to come to America. We didn't care where- at least my parents, I was too young to know, but that was it. Then we had a large Persian community in Dayton so we were very lucky for that. And I guess what they were doing then was recruiting doctors from other places to come to, I wouldn't call Dayton rural, but not like New York, LA Chicago.

L: So what was your interaction with the Persian language growing up? I'm sure your parents spoke it to you. Did you speak it back?

M: I did mostly. It was my first language. It's not my best language. My first word was daregee, which I was sick.

I guess I learned how to say thermometer, but it's actually not an easy word. But I learned Farsi first and then Greek and then English. Basically my native tongue is English and I grew up in a household where there was a lot of them speaking in Farsi and me answering in English.

L: And you had a sister.

M: Yes, and even with all the Iranian friends that we had we would mostly speak English. I have some friends who grew up in LA and don't never have never even been to Iran. And their Farsi is perfect, but they grew up around all these Iranians.

And so I just didn't get that. I got the kitchen Farsi every time. I remember I did an interview in Farsi once with Voice of America. And afterwards she's like, hāla englisee. How embarrassing! Cause I worked so hard to know the right words and I don't know how to say human rights, hoghooghé bashar. Like there are many fruits I know in Farsi that I didn't know in English- those are useful things. I eat a lot of fruits, so...

L: And then what about reading and writing?

M: So we had a Farsi class. And that was just a group of our friends. It was like me, Nobar, amir and Allie. And so the four of us were in this class and it was very funny.

We would read out loud. I'm dyslexic. So like the reading out loud in English is bad enough and I'm just a slow reader period in any language, English, Spanish. And I just was, I hate it. I hate reading out loud. Part of it was tough.

L: And what about culturally? Did you feel like you were Iranian growing up in Dayton?

M: I thought I felt very Iranian just because we had that community and there was no school I ever went to where I was the only Iranian and that's because of our community. And also there was no school I went to where I was the oldest, there was always an older Iranian cousin. We weren't all related, but they taught "your cousin." All the teachers had one of my "cousins," if not my sister. My sister's older than me as well. But I do remember in middle school, my best friend I was talking about, w We were talking Farsi one morning.

Her coat that night caught fire. So it was like drama of her coat having caught fire. And so we're talking about that and my advisor was like, stop you can't speak another language. You have to speak English. Because she thought we were talking about her.

It wasn't, we weren't talking about her, but after that we started talking about her. And so I was basically in middle school, forbidden from speaking Persian. I've always been rebellious when I'm told not to do something. I really want to do it. That was very good for my Farsi. And in college, my Farsi got really good.

I had a friend Roxanna who she came to the U S when she was 13 Her English is great, but her Farsi is perfect. So my Farsi got really good in college, but then the more people I'm able to talk to here in Wilmington, I lived on the coast in North Carolina. There are very few Iranians. So I've hunted a couple other professors out at my university and we're trying to get together more.

L: Got it. And so then chronologically, so you've got married to an American, so you have a different culture in your household. And then how old were you when you started doing the study of Rumi with your father?

M: Thirties, late thirties. Yeah, so, old. I wasn't young. At that point, it took me a long time to figure out like, basically it was the recognition that like, he's not always going to be here. I rely on him for so much when it comes to that sort of thing. And since I do love the poetry, I would frequently go to the poetry and be like," Ahmad, what is the," my dad's name is Ahmad. I call him by his first name. "What does this mean? Can you explain?" He gives these like long explanations and I have access to not only the poem and I can send him poems.

Like people send me poems and they're like, where's the Farsi of this, about at least 10 to 20% of the time, the Farsi doesn't exist. But he has this mentality of know that, whatever that is at its heart it's Rumi.

L: So Coleman barks, for example, he's not anti Coleman Barks?

M: He loves Coleman Barks.

L: Okay. Interesting. Cause I feel like there's a lot of controversy behind that.

M: It's a lot of drama around it, but I will say there's a difference between appropriation and appreciation. I think for him, like I, there was a part of me that feels like it's stolen, but also I never wouldn't would have written this book if it weren't for Coleman Barks that, growing up with Molana and Hafez and Saadi and all of that there are way above my head.

I would never have the nerve to say, I'm going to translate this poetry and I'm going to learn this poetry in Persian. Once I realized Coleman barks didn't even speak Persian, I was like I can do it. If he can do it, then I definitely can do it. It's suddenly I had permission.

Which I wouldn't have had otherwise, I don't think I ever would've approached something like this. It's too hard.

L: I like that. I actually, someone called me who was doing a study about Rumi or something from a university and asked my opinion on Coleman barks. And I had the same takeaway.

It seems like he feels it, he's tapped into something and he's written it in a way that's really accessible to people. And I feel like the more like awareness there is about these poems, the better. So if it interests someone in going and picking up a Rumi book, then, and reading the original.

M: Yeah. Rumi even says like ham delee az ham zabanee behtar ast, but it's better to be of the same heart than to be, have the same tongue, same language. And I think what, one of the things that makes his poetry, I do think his poetry., Coleman Barks, his translations are the translations,

although, there, there are better ones in terms. Now there are better ones, right? Daisy is a beautiful, like rhyming translation in terms of accuracy. But I think Americans really related to that. And English speakers in general really related to that. And I don't see why to take that away from them.

And they're not like direct. Yes, he wiped the Islam from a lot of it. I think he was trying to get with English-speaking audiences who were majority Christian. So the stories about Jesus come in and not so much of the Mohammed. So it's not quite the same, but still, I'm still grateful.

L: So tell me about the like specifics of your study with your father. Did you study whole poems? Was it just the snippets that he was giving you? Or how often were you all studying?

M: So I went to San Diego where they live and was spent an entire time, never in my adult life spent a month away from my husband, let alone a month with my parents. My parents live there.

So that was an interesting thing, but it was for this purpose of learning the poetry. And I was like set for classes and he was like the same. He's always been, the classes are everywhere all the time. And I was always trying to write things down and he was always shutting my computer. He was always saying, just listen to it.

And these were the poems I chose that he has repeated more times than any other poems. So it's cool for me to have this book because all of these poems are my dad's favorite poems, so it's really cool for him. Cause he has all his favorite poems together in Farsi now as well.

It's really being able to connect that way was great. But I did try and do these two hours every morning, we're going to do class, but oh, there's a golf lesson or come with me to the boardwalk, like to take walks every day. The best lessons never came, this is the lesson of life in general, when you have a pen and paper and waiting for them. The book took a lot longer to write than I either anticipated or wanted at the time. But ultimately it took as long to write as I needed to write it.

L: And so how does your study continue now? Are you still reading these poems? Do you have a lot of the memorized?

M: I have a good amount. Not like my dad, I have a few, but there's some that are for me have become mantras, like one that has become a big mantra for me. And I don't even think this is a couplet, or just half a couplet.

And it's a zar talab gashtee khod aval zar boodee, which means, you went out in search of gold. My translation is you went out in search of gold, but all along, you were gold on the inside. And that is the, like, whenever I'm in a place where I feel like I don't belong or I feel like people are judging me, like before an interview this is my way of remembering that not only am I gold on the inside, but these are the people from whom I descend, but people who wrote something like that, these are the people holding me up.

And even if I think I'm, Not smart enough for whatever thing it is that I'm supposed to do. I know that I have a base of, ancestors who are a lot smarter than I am holding me up. And that's what I come from. And that's part of the message of the book as well is to go back to your own culture.

L: I actually, yeah, I wrote down all the themes of the book and I was like, man, we could have a podcast episode about each one of these things because you also talk about how you grew up feeling disconnected from this Iranian culture, especially when you went to LA and you were around these Iranians that like look a certain way, or, we have these stereotypes of the LA Persians and I completely related with that.

We also had a big Iranian community in Dallas, Texas has a lot of Iranians, but I always felt so weird among the Iranians. We had all these beautiful girls in high school who knew how to do their hair and knew how to do their makeup.

I just felt so different from that. And then it wasn't until I came to college in Austin, that I was like, oh, I think I'm just a weird Iranian. And there's a lot of weird Iranians and I met them all. And it's just, you're not going to relate to everybody in your culture, just you're not going to relate to everybody in the world that then you like find your people.

So I really related with that. And I actually, I don't know, I wrote this quote down. I don't know if you read this Samin Nosrat recently wrote, I struggled for so long to find the best way to relate to my heritage, my whole life I've I haven't been Iranian enough for much of my own family or the right kind of Persian woman, whatever that means, for other Iranians and ever since my show,

I faced nonstop scrutiny from Iranians about all the ways I'm doing it wrong. Just one small reason I don't read comments or messages. It can be hard to love being Iranian when it feels like Iranians don't always love me back.

I was like, oh, I totally, I feel that completely. I feel like a lot of us feel that, and you expressed it really nicely in your book of like being surrounded by your people and just feeling different and feeling like you talk about things that they don't talk about openly.

And so I really appreciated that in the book as well.

M: Oh yeah. Thanks. I hadn't seen that post, but I'm going to go back and look for it.

L: Yeah. I found that very heartbreaking, but I also feel recently for me. I feel like just through social media, I know it has all its downsides and everything that I do feel like I've found a lot of people like Samin, the weird Iranians out there.

M: I feel like it's the ones who never got plastic surgery.

L: Maybe that's it.

M: I'm not sure if that's it, but I do know like neither me nor my sister has ever received the nose jobs.

There's that, and also there's the whole theme of of, the stereotype of Iranians being doctors and lawyers.

That it's really wonderful to hear that your parents, despite being doctors themselves, like created this platform for you, you got the education and then now they're have you pursuing your passion.

Sometimes take some time to get to that point. But I think, t h e only reason I wanted to be a lawyer and I wanted to be a lawyer since I was a kid was because I've always been interested in justice.

That's been the thing I've been best at something is unfair and happening in front of me. You can bet I'm going to say something. Hands down. So that's one thing that I'm really good at. And I will not shy away from speaking, if I see something that's unfair and trying to fix it.

And I thought the legal system was the best way to do that growing up. And then once I got to law school, I wanted to be an international human rights. Which I, God bless the international human rights lawyers doing this work, but you have to fail every day. And if you could enforce international human rights law, then we wouldn't have half the world leaders.

So it's just a very unenforceable difficult thing to do. And, being somebody who's for me, writing was a much faster way to change the world than law, because I knew even no matter how much I practiced, it's not like I'm going to change the law or fix. And even if I do change the law, it doesn't mean anyone has to follow it.

And to change the law, then I would have to go into politics, which I definitely don't want. But with writing, like you can change people's minds with words like power and I really think. That level of power is just, it's amazing. And it's with art in general, whether it's words, or like Samin with food.

A nd those are the people I've really related to and connected with. And it's really hard in our community to be an artist, to do that for a living because it's in Iran, it's not a job, it's a hobby. Even the book being translated into Persian, because of sanctions, I'm definitely not making any. Yeah. We're going to the second printing. I am making no money from it, but thank God, the publisher who deserves everything and the translator, they deserve all the credit for that. And it makes me feel good that there are people in Iran making money off of it- not making a huge living off of it, but something.

When I came to my parents and was like, I want to stop practicing law. Do this full time, it wasn't something I did before I had an advance that was able to support me. Once I had that advanced with my second book, when I sold my second book. It was, even to me, it was just such a large, I it's not a ton of money, but it was for books, a lot of money and I did, I'd never thought that was a possibility for me to just be able to make a living as a writer.

And once that was possible, then I went to my parents and I was like, okay, I want to do this. And then I was like, by the way, my agent just told my book for guests how much? And they were like, okay, and it was also that book was about having bipolar disorder. So it was there, there was also this notion of do you want to put yourself out there? Do you want to add to the discrimination you're facing in your life? But I, as an activist, I think mental health is a civil rights issue, especially having been held in solitary confinement and things like that. It was important for me to speak up about it.

And because I had the personal experience, I was down for it. They just thought I would lose credibility, maybe in certain circles I did, but I think more than anything, I gained it. Because once you say I'm dealing with mental health conditions, whether it's in a serious mental health condition, be a bipolar schizophrenia, frequently people will be like, oh yeah, my sister or my brother or my mom, or me.

They only tell you that if you tell them and that has been the gift of that book is that I've been able to learn that there's so many people with serious mental health conditions who are living and surviving. And that's a huge gift. So in so many ways the book gave back to me and allowed me to like finally make a living doing this thing I love doing.

I don't love doing, I love having written. I don't love writing all the time- any writer who says they love it all the time is I feel like lying. I want to believe that they're lying because it's work.

L: You have to put it out there and people have to read it and judge it. And it's really hard. So I very much admire that you do this. I feel like with being a lawyer, you win some trials, you lose some, but it's not like in this public forum where everyone can just like, look at you.

M: And yeah, I basically, with my first book, I got death threats and rape threats.

L: And it was about being Muslim in America?

M: Young Muslim Americans. And I included two queer Muslims. In that book, I'd written about a dozen young Muslim Americans, including myself. One of which was bisexual, the other one was gay. And I had my, one of my professors at law school was, is like one of the leading experts on Islamic law. And he wrote the preface for it, for me, which is huge for him, for somebody who knows Islamic law to do that was I always a huge gift.

And then to have that book come out and then to get these death threats, you realize that, take it as a compliment. Although for the record, I now report all death threats. Back then, I didn't know. I just deleted them. I was like, no. Wow, thank goodness. They all seem to come from the UAE0 my husband did some investigating.

B ut it was being hated from both sides being hated from like my fellow Muslims for being too liberal and whatever. But, not from by non-Muslims or just the whole reason I wrote the book first place.

L: You were saying, you can change the world by writing books.

You have a really nice anecdote about this one woman that you saw that you asked, what does the Muslim supposed to look like? And that led her to a journey of reading your book and it changed her trajectory. She gave it to her whole family. That's just amazing. That's just one example that you saw.

I'm sure there's countless people like that. But now having gone through this journey and having learned these poems I want to ask what your view is of learning the Persian language. We've talked about Coleman Barks, you can be ham del- do you think it's important to read these.

In the Persian language. Do you think it's important to learn it? What are your views on learning Persian?

M: Oh my gosh. Yes. I think it's important. I have a niece right now who is a freshman at Duke in undergrad and she's taking Persian classes. She didn't really grow up speaking much Farsi.

So she doesn't really know it, but she's learning it and watching her learn and being able to talk to her is, has been extraordinary. And for getting to a point where, I've, since the book was published in Farsi, now I'm able to do events in person and meet. I've met with a book club full of Iranian women, even before the book was translated.

They read it in English as like an exercise. They had a different chapter and there was a great, amazing book club and to be able to connect with people in Iran, which was huge for me. And my hope is that the wayWay of being able to go back safely at some point because of the work that I've done with the queer jihad movement, not entirely safe, but yeah, but I'm working on it.

And because even in the translation, for instance, they, there was some censorship. But it was more important for me that the book be available to people inside of Iran, then it be identical what it was in English. And it's pretty close, but yeah, it was hard for me. It was it was very hard for me to pull out, like there's a reference to how Molana's poetry is like part of reflective of so many different faiths.

And there was a reference to like Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, Christians, Jews, Jane, like all these different faiths, including Bahai's, and they took that citation out, which gets under your skin.

But you were saying your niece is learning Persian.

L: And why do you think it's important to know the Persian language?

M: I think if it's part of where you come from that's something, there are certain things that you can say. And you do such a great job in terms of teaching, like funny sayings there, because it's part of a culture, right? Like when I'm signing, I sent an email, I think we sent maybe two or three emails that I sent the latest one, I had written on it at the end, ghorboonet beram. Let me sacrifice myself. Not like standard, but we're both Iranian. So I think it's a way to connect with people that like, we can connect in a way. A lot more quickly, a lot more easily because we share a language. And so you understand things like that.

You understand things like tarof. And without understanding the language of 'ghabel nadareh'. And it's just the richness of it. And I think this is maybe one of your recent lessons I was looking at was ' delam barat tang shodeh'- I miss you.

Like my heart has become tight. Yeah. Literal translations of them are so sweet. So like just for the idioms, but I think it's a way of connecting with your culture and your background, where you come from. And that to me is a kind of healing.

L: Or even these poems, you'd mentioned a poem in the beginning that you had the translation for, but you were like, oh, there's this one word though that we can't translate.

I feel like those are the ones. When I read these in Persian, there's a lot of words in there that like you I don't know, I have to look up and like they have Arabic roots are there. They're just very difficult words. And after a while you learn, you unlock this key and you learn how to decipher them, but there are just these words in poems that will knock you out of your chair.

The more you think about them, like that happens. All of a sudden just hits you the gravity of this poem. And I feel like the translation just doesn't do that. You can understand that the meaning behind it, you can understand the feeling, but it doesn't knock you out of your chair the way that one Persian word does, exactly.

M: Yeah. And it's like home, your heart knows that your soul knows that. Rumi is always saying, go to your source. And it doesn't mean your source as in the country you're from, but that's closer, right? That's part of your source. But also as in the more you go back and I write about this in the book, this notion of like intergenerational trauma, which all of us, we're part of a diaspora like that.

Of course we raised with war and revolution and like colonialism and all of that, but we made it. We're still here. And that to me is a testament to intergenerational resilience. And that going back to your own culture is part of that. And I see Americans as an American, like I see other Americans who are like, let me run off to India and go to an Ashram.

Somebody with like Irish heritage- and there's nothing wrong with going to India. I just feel like if you're Indian, that's a great place to go to find yourself, but you have this rich Irish heritage and history. It's not like you don't have your amazing poets.

That's interesting to me that you would go try and find yourself in a totally separate place. Not that I don't value, like going to different parts of the world. I just feel the path for me to the beloved is shorter in Farsi is shorter as a Muslim because generations and generations of people before me, that's how they got to the beloved.

L: Amazing. I love that.

M: So it's just a shorter path. It's not that it's the right path.

L: What is your hope for the Iranian diaspora? At this point in time, where do you see us going? Or what do you see our journey as being.

M: I hope we can all go back safely to Iran.

That is a big hope that we can all do that. I will say the most offensive Islamophobic questions I have ever received. ,at events online in comments with relation to Islam that are the most offensive have always come from fellow Iranian.

And I know it's from a place of trauma because they accept the Islamic Republic's version of Islam, which is not Islam. So of course, like they're been traumatized by it. They have a history that I don't know what it is, but they're standing up in the middle of an audience and saying something, but I'm like, God, this is my own people.

And are like encouraging war with Iran. Like it's easy to encourage war with Iran when your family isn't still there. My parents just got back yesterday, but you shouldn't have to have family to know that they're human beings living there who through that. And no change can happen from the outside, like real change happens from the inside.

And we can be supportive as a diaspora of Iranians within Iran who are doing that. But we can't impose it. Like obviously Americans tried to impose it many times. It doesn't work. Never would have had an Islamic revolution if it weren't for the coup right in 1953.

So that history is important to recognize, but for the diaspora I hope that we're humble. I hope that we, and I feel very bad specifically for Iranian Muslims, because they've really been in their faith. Like I see Iranian Jews and Bahai's , and they have a sense of faith. Very strong Iranian Muslim.

Not only sometimes do they not have a sense of faith? I've never met more evangelical atheists. That's who you want to be. Like, that's fine. But there's something like divine and beautiful in this poetry. That is really, Rumi was an Islamic scholar. This is not just coming, in some of it is just direct translation from Arabic to Farsi of the Quran.

Our faith is beautiful too, but it's been stolen and manipulated very much. I live in American south. I see a lot of my students hate Christianity. And I can't tell you how many red letter Bibles I've handed out to students to be like, this is look what Jesus actually said to what they told you for yourself, learn for yourself.

And that was the gift of being in the diaspora was I was able to do that for myself, but I recognize that those Iranians who were in favor of say war with Iran or in favor of sanctions or things like that. A lot of them are speaking from a level of trauma that I don't know and can't understand.

So my hope is that we can be empathetic toward one another and not mean not promote killing one another, promoting sanctions or war or anything like that. And hurting one another, like fighting amongst one another, that I really hope that for the diaspora and for this idea that there's only one space for us to, is there is a writer.

Like I want there to be more Iranian writers. I don't want this to be less. So like it's important to me to help other Iranian writers who want to do that. Cause I know how hard it is to want to do something that isn't doctor, lawyer engineer.

L: And so to end I should have probably asked you to prepare for this before, but is there like one poem that you would recommend, like maybe to someone who's not familiar with Rumi's poetry.

M: To start with, to dive into Rumi the start of the Masnavi, the first, I think 13 lines of the poem about the name, the reed bed that I think. That's the one that strikes me as a great place to say

L: It's perfect because we do have a whole lesson on it.

M: There's also an, I don't know where it is. It might be in the Masnavi. It might be in Divané Shams, but there's a poem. Especially a lot of us are searching this he says, and I'll say in Farsi, and I'll probably not remember the translation, but

A y ghome haaj rafteh kojayeed kojayeed, mashoogh hameen jast, beeyayeed, beeyayeed . And so this is like Rumi talking to people who are going for Hajj, and he's like, all of you were going to for Haaj. Why are you going to. Far away when the beloved is right next door. And there later, he said he talks about being right next door. But that notion of you don't need to go anywhere.

You don't need to search for anything, like everything you need is already within you. And that is what speaks to me most about his poetry, but in terms of learning it for the first time, and one of the things I love about that there's a line and I, I can't tell you the Persian of it.

He talks about majnoon, which is that's a whole other lesson. But he talks about the lesson of the Reed flute is reserved only for those who in madness reside. Obviously that hits me really closely. And I guess it's classified. And I, my translation was like, this lesson is classified.

It's only for those in whom madness resides. I buy that a hundred percent in that madness, rooted in love.

L: And the book ends with talking about love. And I loved the ending. I won't spoil it for people, but they should definitely read it because it really all boiled down to love all these poems, language, everything.

The love of your father led you to this love of this poetry and to, healing and all of that. So again, I want to thank you for this wonderful book. I really appreciated it. I really loved reading it. I related with so much in there and I encourage everybody to read it.

And can you just tell us where can people find the book and where can people find out more about you?

M: Yes, it is available wherever books are sold. I encourage you, if you can go to bookshop or your local independent bookstores, if you can afford to do that and support your local independent bookstore, I really encourage you to do.

And bookshop is a great website to be able to figure that out. If you don't know what your local independent bookstore is, but you can buy, you can also buy it at Walmart. And the, in terms of getting hold of me I'm on Twitter.

And I have a newsletter that I haven't sent anything out for like more than a year. So if you want to sign up for a newsletter that only comes once the book came out.

L: I have to say also an interesting part of the story- you covered everything in the book, except for the pandemic.

M: There was a part about virology and the book that runs through there is actually a part where my dad talks about how humans think that they're so big, but a little virus could take them out.

As the pandemic started the book was so helpful for people. And I'm so grateful for that. Obviously. It's not the best- my tour was canceled. Everything was canceled. But it came out.

What I found in my life consistently is that the Beloved's timing is always better than mine. I never would've chosen that timing if I knew, but it was better than what I would have chosen.

L: All right. Thank you so much, Melody. And that was so fun and I still have a million questions, but over time, think, thank you so much for talking with us. And again, There will be links to all these things that we talked about, including the book and Melody's Twitter and Instagram and all that stuff on the show notes for this Seth for this episode.

So thank you so much and good luck with the rest of the writing. Thank you so much, Leyla jān, take care. Thank you.

Related Links:

- Purchase The Rumi Prescription from Book Shop

- Melody Moezzi Instagram

- Melody Moezzi on Twitter

- Rumi's Beshno een nay