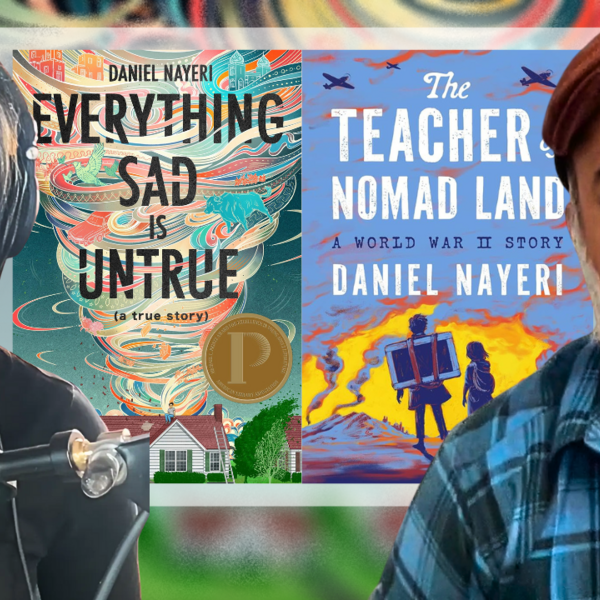

Growing Up Irooni – From Oklahoma to Shahnameh: Daniel Nayeri, Author of Everything Sad is Untrue on Memory, Myth and Belonging

In this deeply personal and wide-ranging conversation, Daniel Nayeri, author of the acclaimed autobiographical novel Everything Sad is Untrue, talks about growing up as an Iranian refugee in Oklahoma, the mythic structure of memory, and the stories we inherit—true or not. He reflects on what it means to carry generational trauma, how he began writing the book in a Brooklyn bathroom, and the long journey of learning to tell his family’s story with emotional honesty.

We discuss the magic of Persian storytelling traditions, from Shahnameh to Khosrow and Shirin, why he originally wrote the book for adults, and how his father reacted to seeing himself as a character on the page. Daniel also shares a preview of his newest novel, The Teacher of Nomadland, a literary adventure set in WWII-era Iran, and why he wanted to sneak a Farsi lesson into the heart of it.

This episode is for anyone who’s ever tried to make sense of a fractured past—and found something beautiful in the pieces.

📚 Related Links

- Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri (Amazon):

https://www.amazon.com/Everything-Sad-Untrue-True-Story/dp/1646140001

- The Teacher of Nomadland (Preorder):

https://www.chroniclebooks.com/products/the-teacher-of-nomadland

- Daniel Nayeri on Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/danielnayeri

- Daniel's publisher:

https://www.levinequerido.com/daniel-nayeri

Q+A with Daniel Nayeri

Leyla:

You’ve said that you worked on Everything Sad is Untrue for over 13 years. Where did the book actually begin?

Daniel:

“In a bathroom in Brooklyn, actually. My dad called to tell me my grandfather had died. I was 28. And I realized I had always thought I would go back and ask him to fill in the parts of our story I didn’t remember. When that door closed, I started counting the memories I had—and that’s where the book begins.”

Leyla:

You originally wrote it as an adult novel?

Daniel:

“Yes. The first six years I wrote it as a grown man in New York, trying to make sense of everything. But it wasn’t working. A friend finally said, ‘Why don’t you just write it from when this meant something to you?’ And it clicked. When I rewrote the scene about letting go of Mr. Sheep Sheep at the airport as a child, that’s when the story came alive.”

Leyla:

There’s a running thread in the book about the unreliability of memory—what’s true, what’s myth. Do you feel like you had to let go of some of that pressure to “get it right”?

Daniel:

“Yes, absolutely. Memoir is inherently flawed. I say in the book, ‘A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.’ But that’s all we have. And I think we do a disservice if we try to clean it up. Everyone remembers differently. I’m certain I’m right—but so is everyone else.”

Leyla:

You’re now writing a new book, The Teacher of Nomadland. What inspired it?

Daniel:

“It’s set in 1941, during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It’s about two orphaned siblings who escape into the Zagros Mountains with a blackboard, trying to take over their father’s job as a teacher. I wanted to explore how war and language intersect. The original title in my head was Bābā āb dād. Three words. But in Farsi, it’s a complete sentence: Father gave water.”

Leyla:

Your father plays a complicated role in both your life and your work. Has he read the book?

Daniel:

“He’s had it read to him. He thinks he comes off great. He’s incredibly charismatic—he can charm a room with a piece of baklava. But no, I don’t think he really sat down and read every page.”

Leyla:

You talk a lot about food, smell, and family stories in the book. Have you been able to pass that on to your son?

Daniel:

“I’ve tried. My son’s twelve now. I didn’t want his first encounter with my story to be through a book where I’m made into a character. So I tell him the stories directly. That’s something I hope he’ll carry forward. Not because it’s nostalgic—but because it’s human