Poetry /

Rumi's deevané shō

In this intro lesson for Rumi's deevāné shō, we go over the full poem with musician Fared Shafinury.

In addition, we learn about Fared and his project ‘Radif Retreat.' In this particular lesson, we also dive into the musicality of the poem and how to interact with it rhythmically.

Watch Fared's performance of Rumi's beautiful poetry on his Persian After Hours performance, live at the Getty.

Watch Now

View audio version of the lessonGREETINGS:

hello

سَلام

how are you?

چِطوری؟

Note: In Persian, as in many other languages, there is a formal and an informal way of speaking. We will be covering this in more detail in later lessons. For now, however, chetor-ee is the informal way of asking someone how they are, so it should only be used with people that you are familiar with. hālé shomā chetor-é is the formal expression for ‘how are you.’

Spelling note: In written Persian, words are not capitalized. For this reason, we do not capitalize Persian words written in phonetic English in the guides.

ANSWERS:

I’m well

خوبَم

Pronunciation tip: kh is one of two unique sounds in the Persian language that is not used in the English language. It should be repeated daily until mastered, as it is essential to successfully speak Persian. Listen to the podcast for more information on how to make the sound.

Leyla: Learn Persian with Chai and Conversation Rumi's Tasnif-e ussaq with Fared Shafinury. Salam be hamegi! We're here with Fared Shafinury to talk about a really lovely Rumi poem. Salam, Fared jan.

Fared: Dorood dorood

Leyla: For those of you who've been with us for a long time, Fared is a long, long, long time friend of the show. He wrote and composed our theme music. We've done several, poetry lessons together and a lot of collaborations together, so I'm excited after a few years of hiatus to be back doing this poetry lesson together.

So thank you so much by for doing this.

Fared: It's good to be back, Leyla. It's good to be back with all of your lovely listeners.

Leyla: Yeah, so we're calling this series. This is the first of this series called the Radif Retreat Series. So first of all, tell us what is Radif Retreat?

Fared: Radif Retreat is my online school of classical Persian music.

It's the Online Institute of Classical Persian music, and we call it the Radif Retreat because Redif is the name of the Immaculate Collection of persian rhythms and melodies and a 12 series of modal system that we have. And, classical Persian music is at the heart of it. And retreat we call because we get together once or twice a year in beautiful locations, and we study and we create music and we have a concert by the end of the week.

So it's a year long program and it's lovely to bring it to Chai and Conversation, finally.

Leyla: That's right, and Fared and I have had a very long history of collaboration and what we do goes really well together. So , the music classes that Fared has are all about community connection and understanding culture through music, through poetry.

And that goes hand in hand with what we do at Chai and Conversation, which is exactly the same goals, community building, learning this culture, this beautiful culture through the language. So this, Radif retreat series of poetry is another collaboration together so that we can pursue these same goals.

So, That's wonderful. So, either you are watching this as a video or you're listening to it as an audio lesson, but if you can see on my screen, we have a booklet that Fared put together for his show in summer of 2022 at the Getty Museum, where he put several Rumi poems to music.

He translated them, produced this booklet. Can you tell us more about this Getty Show?

Fared: Yeah, it was an honor to to work with the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. And this last summer I was invited to be a part of a series called Persia After Hours. We were actually the first musicians to, to play at the Getty Villa and their outdoor, Greek Roman amphitheater.

And it was a lovely, lovely evening with a beautiful community of Iranians and non Iranians coming to celebrate our culture, but also celebrate, what our culture has always stood for, which is an essence of radical inclusion and love. And every time we read Rumi's poetry, we always feel this unabashed sense of falling in love all over again.

And my goal was to bring this message of love and inclusion through the words of Rumi, through music and dance. And, we were happy to get together that night with, all of Los Angeles.

Leyla: And with your graphic designer, you put together this book as well. Can you say, who is your graphic designer, who's also a longtime collaborator of yours?

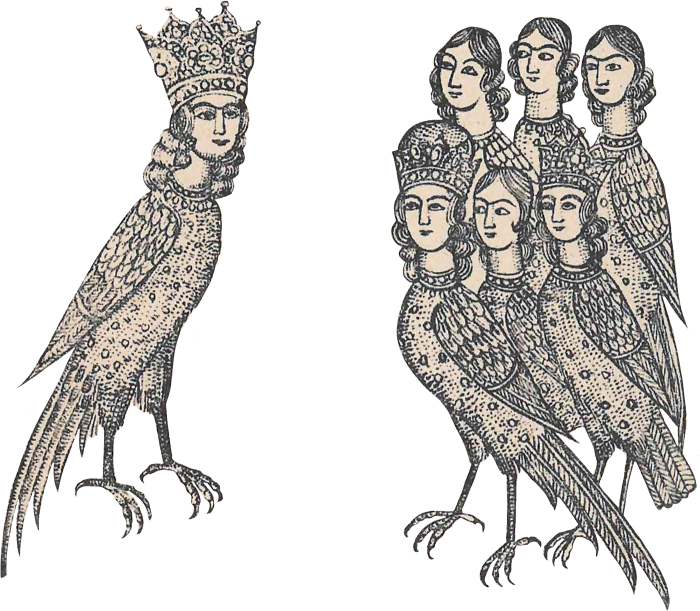

Fared: Koroush Beighpour, which is a dear, dear friend of mine. Him and I have been working together for almost a decade where he's done these beautiful graphics, that bring my work to life on paper. As you can see here, this booklet. Called Mashough, or Beloved, which was the name of the show.

He has done a beautiful job with calligraphy, and I'm sure if you look through the entire booklet, you'll see the immaculate, detailed work

Fared: He does.

Leyla: And as an introduction to this poem that we're gonna be going over today, and an introduction to, why Rumi was such a central figure to this series, could you read the introduction to the show that you have in the beginning of the book?

Fared: Throughout history, there have been beacons who liked the way for others to follow. Rumi is one of them. He writes of a limitless, eternal love that is all encompassing and void of judgment. This yearning for the beloved mirrors our most basic yearning for love, for the awe and majesty of nature, and for the deepest, most intimate relationships we cultivate throughout our lives.

Centuries of classical Persian poetry have explored this boundless love. This concert is dedicated to this ancient wisdom that still survives and it reverberates today. Let's celebrate a history of inclusion documented through poetry and live in the spirit of the now, embracing the essence of unabashed love.

Leyla: And you used that word inclusion and all encompassing a lot. What did you mean by that? Can you expand on that a little?

Fared: The concept of the beloved, whenever we come up, when we hear that word, in Rumi or in Hafez or Saadi, it really evokes this feeling that this is a lover. This is a physical form lover.

Lover, like a girlfriend or a boyfriend or someone that you think they're having a romantic relationship with. But yet the way that it's expressed, it's also has a divinity behind it. So the personification of the love for the divine. Through a physical relationship and how they're one and the same really brings about this essence of inclusion and non-judgment.

So for me, I dedicated this message of Rumi and the month, the pride month of June, last summer, to bring about this era , of non-judgment and allowing people to be and love whoever they wanna love. And to use Rumi as that radical acceptance, that radical relinquishing of the self and, and devotion of this love and not allowing society to make you feel otherwise.

So for me, bridging these words of, of Rumi to today's society, in today's problems, as we see in Iran, woman, life freedom is the, the slogan, the words that has taken all of our hearts and minds with it, and I believe that this is, been in our culture. We have been a free and proud people in our co, in our poetry Is there to show that.

Leyla: Wonderful. Absolutely. So then to introduce today's poem, so this is Tasnif- e ussaq. And first let's talk about the title of the poem and also you, yourself translated the works in this booklet. So you translated the works of Rumi. Can you tell us a little bit about your translations?

Fared: My, my translations oftentimes take on the form of a pro where I'm like slam poetry, just going off on a, on a long sentence, just image after image and trying to express the, the width of, of these metaphors and the dual meanings behind them. But sometimes they're also very lyrical. So in Rumi's case I can go either one or two ways. I have two of his poems that I've translated in this booklet where one of them is in a form of a pro and the other is very lyrical Because of that repetition and, and the, the rhythmic essence that, that goes behind his trance-like way of creating poetry. So, I think the poem that you have chosen for us to talk about today is Tasnif-e ussaq and, and the word I have in the footnotes of this booklet as, as a term referring to a ballad, and ussaq is the plural form of ashegh.

"Asheghan" is another way of saying the lovers. "ussaq" Is a more classical term and a more an older term for the lovers

Leyla: Wonderful. And so what we'll be doing in this lesson is that tha will be reading the Persian. I will be reading his translation right afterwards, and we'll talk about the essence and meaning behind the poem.

In subsequent lessons, I'll be going over the poem word by word, phrase by phrase, and teaching you how to use the words and phrases in this poem, an everyday conversation. So it is my favorite way to teach the Persian language. And it's also with talking with Fared we're also gonna learn about the musicality of the poem, the rhythm of the poem, and that's gonna really add to our understanding of the poem as well.

So, without further ado, let us go to the poem.

Fared: heelat rahā kon āsheghā, deevāné shō deevāné shō

Leyla: Dear lovers, it's time to let go of your games. Be crazy. Be crazy. I say

Fared: vandar delé ātash darā, parvāné shō parvāné shō

Leyla: enter your heart's inferno. Be the moth to the flame.

Fared: ham kheesh rā beegāné kon ham khāné rā veerāné kon

Leyla: Abandon this Loveless society. Vacate your homes of shame.

Fared: vāngah beeyā bā āsheghān ham khāné shō ham khāné shō

Leyla: Join all of the other lovers. Live with the insane.

Fared: roo seené rā chon seenehā haft āb shoo az keenehā

Leyla: Go and wash your heart. Wash your heart of any grudgeful pain.

Fared: vāngah sharābé esgh rā paymāné shō paymāné shō

Leyla: Do not just drink the wine of the lovers. Be also the chalice that it contains.

Fared: bāyad ké jomlé jān shavee, tā lāyeghé jānān shavee

Leyla: Do not just mingle with the spirit. Allow the beloved to flow through your veins.

Fared: garsooyé mastān meeravee mastāné shō mastāné shō

Leyla: For if you approach these drunkards down at the taverns, go and be drunk. Be drunk, I say

Fared: it's truly the only way to approach a drunkard down at the tavern. We know this at our Austin local-- Justine's bar.

Leyla: That's right. Okay. So, tell us just the general idea, I think as someone who just hears the poem, first of all, I heard hope you heard all that repetition that was happening as if you're just going in this circle.

It's a little hard when we keep interrupting it with the English translation. But Fared, what are your initial things that you want us to notice about this poem?

Fared: To throw back to our first Rumi poem, you and I did Ruz-o shab. We remember that there was this repetition within that poem, so this is really a hallmark characteristic of how Rumi draws in his listeners through this trance that he creates with the repetition.

If we can just focus, for example, the endings of these lines. deevāné shō deevāné shō parvāné shō, parvāné shō. ham khāné shō ham khāné shō, and finally with the last mastāné shō mastāné shō. So that right there is part of the musicality of how lyrical these poems are.

So if we start off with how we're gonna read this to really fall into a rhythm or rhythmic cycle again these can be expressed rhythmically and in different ways depending on where you're stressing in the poem. But one of the plays in classical Persian poetry is on the consonants versus the vowels.

And if you notice with my hand gesture, I tighten up with the consonant and with the vowel I express and I elongate. So one of the ways you can really fall into the musicality of Persian classical music, we start off with the first line, and we could do this as an example.

So let's just focus on those few words. So with the word rahal, it ends with an rah that allows you to really express yourself , and stretch that vow.

So here we're seeing that it's repeating itself: deevāné shō deevāné shō

Understanding where these vowels sit within the lines with these poems, and if you read them at first, I'm sure you're gonna be rusty going through it slowly, but over time, as you practice this to bring a musical sense to it, you'll notice that these vowels will pick up on themselves, and you're gonna fall right into it "

ham kheesh rā "

again with,

kheesh

now we have the"ye" in the middle of the term "kheesh", we're in the second.

ham kheesh rā beegāné kon ham khāné rā veerāné kon

So now I'm gonna keep a meter. We're gonna try this with a meter. One, two, ready and-

heelat rahā kon āsheghā, deevāné shō deevāné shō

vandar delé ātash darā, parvāné shō parvāné shō

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. So this falls into a six eight rhythm. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

So here you notice how the rhythm really just pops out after you, you focus on where these vowels are and where the consonants sort of close in.

Leyla: Yeah, that wasn't what I was expecting. When you started the rhythm. That's interesting. So I think for someone who doesn't understand the language at all, you can listen to what Fared was saying, just understanding the rhythm of this.

And you, you get a sense of the poem a bit even if you don't understand all the words. And that's, that's one of the beauties of it. And this has been also sung on by a lot of different singers as well, right?

Fared: Yes. It's been, it's, it's one, it's a very famous poem of Rumi and. Actually one of the more memorable versions was sung by a Tajiki artist from Tajikistan, and with his most endearing and sweet accent is a Tajiki accent.

Leyla: They sing this very beautifully, which, yeah, we'll link to that too so that you can listen to it. But going into the language aspect, let's, let's read the first line. There's a lot to talk about language wise in this poem. So can you read just that first line again?

Fared: heelat rahā kon āsheghā, deevāné shō deevāné shō

Leyla: So let's even talk about what does the word 'sho'? What does that mean? We see that all throughout this poem. So let's start there.

Fared: So the term "sho" is to be, to become,

Leyla: And it's shortened from "besho" so become, so you become, so it's talking about this actually it's talking about the concept of what is, what does " ashegha" mean? You've translated as lovers.

Fared: If you so dare to be a lover, then this is how you must be. You must relinquish your, your tricks. You must relinquish your games. You must relinquish your shame. You must wash your heart of all grudgeful pain. So here Rumi is, is is addressing society. He's addressing people who claim to be in love, people who claim to have a relationship with the divine people who claim to be good Samaritans.

And, and, and again, it can, it can really lend itself to so many ways of understanding, connection, either to the divine or to a physical love. And here āsheghā really is addressing everyone.

So the direct translation of āsheghā is lovers, but we really don't have this concept in the English language, which is the first example in this poem of why it's so important to know a language or a poem in its original language.

When you say lovers in English, it doesn't pertain to everyone. Not everyone can be a lover. What is that? I guess sometimes you say oh, he's a lover. She's a lover. It, you can use it in in language, but like you're saying, it's saying in this poem, āsheghā is this class of people who have chosen to be lovers.

They love.

And, and, and for me, the, the closest thing in America would be the transcendentalist movement with Henry David Thoreau, for example. When, when I, when I read Walden Pond, for example, the way he addressed society is very much similar to the way Rumi addresses society. And, and this concept of, of being a lover in Persian does, does really demarcate us in a way because Iranians really pride themselves on being lovers.

And, and that's right. And not just in a physical sense or in an earthly sense, but, but this this connection we have with the divine, with, with the essence of being in the moment. And I, and I think Rumi here is, is basically saying if you see yourself as a lover, then you must relinquish these tricks and these, these masks that you've been holding yourself to.

And, and here in this poem, you, and that he. He goes through each line and he's, he's hitting you with, with a show, basically giving you advice, be, be this, be this, giving you

instruction. So then deevāné shō ,

so right now in the English language so you're saying be crazy, be crazy. A lot of times, they say, don't use this type of language becoming crazy.

But in, in this poem, Devon showed the concept of being deevāné is not just going crazy like becoming mentally ill. It's not a bad thing. It's saying it in a positive way. Become crazy. And that means losing your ego, right? Losing your sense of self?

It's, it's because in, in the society that we live in when you are pure to the essence of who you are, when you have become childlike, essentially, , you are honest.

You are authentic, you are very much unabashed as, as this term has been coming up, and Rumi is saying essentially, it's almost a bit satirical when they say deevāné shō , they're, they're being a little bit sarcastic in the sense of yeah, be crazy because that's how everybody else will see you. But by being crazy you're actually being the most authentic to

yourself.

Leyla: Absolutely. Absolutely. Okay, so now let's look at the next line.

Fared: vandar delé ātash darā, parvāné shō parvāné shō

And here this motif, this metaphor of the moth to the flame appears again, vandar delé ātash darā. So within the heart of this inferno come out as the flame. Essentially there is a, you're so, you're so, devoted to your love that you will enter the fire of this, you will burn. So this, this relationship of ussuq va asheghan really plays itself out into terms of a moth and a flame.

So the flame is the beloved. And the moth is the ashegh. This is why they, he says, be crazy. Be a moth to the flame, because the moth all sense of like I'm about to burn, leaves his mind because he's just, he's so entrapped by the light. He's so in love. He's so enamored by this that nothing could get between him or her to this devotion of, of the light.

So here, when it says

parvāné shō parvāné shō, it also evokes an idea of the phoenix because you're coming out as you're coming out of the flame. So here Rumi is really messing with you by giving you this metaphor of the moth to the flame. But he's also saying that, no, you're not really burning. You're gonna come out of the flame as the moth.

That's the freeing agency is being the parvāné shō you, you fly. Par is literally a wing. So get wings from this flame. Yes. All right. Next, so here it says, ham kheesh rā beegāné kon ham khāné rā veerāné kon

Here I've translated as abandon this loveless society, vacate your homes of shame, right? Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. But, but a more literal translation is to see the self as the stranger; turn, turn the familiar to the stranger. It's basically saying, turn your world upside down. Every, every sense that you had of what was correct. Turn it around, shake it up a little bit, right?

ham kheesh rā beegāné kon ham khāné rā veerāné kon And then your home, turn your home to the outside.

Leyla: ham khāné your roommate , or is it saying ham...khāné ra?

Fared: your home.

Leyla: I see. Okay. I was taking it as kheesh and ham khane and, but it says ham, also. Ham, the terms of, also yourself beyond, and your home gone.

Fared: But, but as Layla, in Persian poetry, these, these dual meanings exist, right? So you will see maybe not with this specific line, but you will see many different Iranians interpreting these poems and in ways that are somehow not congruent with one another.

But, ham kheesh rā beegāné kon but in my interpretation, and as many that I've taken note from, and, and I've done research, it says,

kheesh doesn't necessarily mean yourself. It could be the people around you or the, the people that are most familiar with you, or it could be your own race, it could be your own, whatever it is you're identifying with that, that you become comfortable with in your bubble. Let it go and go be with the others.

Anything that has been destruction, this is all just about destruction. Absolutely. Let it go, destruct.

Yeah. Let go of, let go of any, let go of your comforts. Let go of your comfort zone. So if you're agoraphobic, leave your house and go into the desert.

ham kheesh rā beegāné kon ham khāné rā veerāné kon vāngah beeyā bā āsheghān ham khāné shō ham . Go and go and live with the, this is where ham khane is someone who lives with, right?

Leyla: Yes. Okay. This is a dual meaning, so ham khane in the first, so ham is a word that means like also equal , and we use it often with different words ham car is your coworker, so it can mean co. So ham-khane could be your co-liver, your housemate.

Fared: So in the first part he's saying ham. Even your house also be gone from your house. Evict. Yeah, evict your house. And then in the second case, it's saying it the way I interpreted the first time, which is go become one with the others. Become a live in the same home as the others.

And this verb "virane kardan" , to, to be, to turn something "virane" means to basically, To go away from . and we see that term often used by expats of Iranians that live outside of Iran.

Our country is now virane, meaning that what was once our khane is now our virane. It's the antithesis to khane, meaning it's no longer a home. It's, it's some place that we have, we have now expelled, or we're expelled from. We're no longer. We, don't go back to that because our house has been taken away from us.

So we, we see that used often. So,so this is that word again. The lovers , asheghan. Come, be, come become one with the lovers. There was that class of society that has chosen love,

right? And, and the first line he's addressing the lovers, people who claim to be the lovers. And then in the, in the second, he's addressing to those supposed lovers that, no, go live with the lovers. Leave your home. Leave anything that you your familiarities and go to the other side. All right?

Leyla: Okay, next.

Fared: roo seené rā chon seenehā haft āb shoo az keenehā

Here we have I, my translation is, go and wash your heart. Wash your heart of any grudgeful pain ero.

roo seené rā chon seenehā haft āb shoo az keenehā So here, when, when they say roo seené rā chon seenehā , go to your heart. Take your heart row, go.

roo seené rā chon seenehā haft āb shoo az keenehā

Essentially saying, take your heart and go wash it. Now the, the concept of haft āb shoo, half is seven. It's a, it is a number that he's using here. There is a lot of meanings behind this. Number seven, it, it pops up. In, in the terms of the seven levels of the sky, the seven stages of heaven, even pre-Islamic, the term seven comes up in Zoroastrianism quite often as well.

The different levels of heaven and that exist And, and you see this here saying half all, wash your heart of the seven. You must go through those seven levels, stages. To, to really relinquish yourself of any grudge. Wash your heart, right? Mm-hmm. Keeneh meaning grudge. Mm-hmm. If I have a keeneh, that means I have a grudge.

Leyla: Mm-hmm.

Fared: vāngah sharābé esgh rā paymāné shō paymāné shō

But take the wine of love and don't just drink it. paymāné the cup. In which you pour the wine. So here Rumi is also saying you must be the vessel.

Leyla: Vessel. Exactly. So, so this word, you'll see it in hava paymā, for example. hava paymā is a vessel in the sky. So this is saying paymā,maho become a vessel.

Fared: Exactly.

Leyla: Don't just drink the wine. But be the chalice that contains. Wonderful. Okay, the last two lines.

Fared: bāyad ké jomlé jān shavee, tā lāyeghé jānān shavee So this line was a more enigmatic one for me that I had to really sit with more than the others because this idea of jomlé jān , to be bāyad you must, you must become jomlé jan. So this idea of jomlé jān, I sat with it for a little bit and I spoke to some, some authorities and, and this idea means jomlé jān means you must discipline yourself to arrive at this purity.

jomlé jān shodan means the sentence of life but, but here, the, the meaning of it, I, I've translated as do not just mingle with the spirit. So something about a divine higher essence of a spirit. Of the self, right? You must essentially become the spirit.

In order to be worthy of the spirit is to be worthy. I am worthy.

tā lāyeghé jānān shavee Right.

bāyad ké jomlé jān shavee, tā lāyeghé jānān shavee

garsooyé mastān meeravee mastāné shō mastāné shō

and I love that line because it's saying it's so good. Yeah. And, and if you choose to go hang out with those that are sitting at the bar, don't go there preaching to them of, of, of anything else. Go be them. Essentially. Many people say that if Christ were alive today, he would be hanging out with those that are drinking and that are having problems in the streets and whatnot.

And, and essentially, I, I find that this. It's very similar. I think Rumi would've been hanging out with different levels of the society that most people probably shun today.

But yeah, it's saying, you're, you're means to to be in search of, it's like a very it's a. Very active process of searching for these drunkards.

So it's saying, if you are searching for the drunkards, become drunk yourself. Become drunk yourself. And that takes us back to the very first line of divaneh sho. So divaneh shodan is losing yourself in, in craziness, whereas mastāné shōdan is losing yourself in drunkness. And they're very similar concepts in this, like in this Sufi tradition that we're we're reading.

Leyla: Yeah.

Fared: Because. Really the, the truest expression of love is, is one in which you don't hold back and you don't judge yourself and you live void of judgment. You, you go forward and, and Rumi here very beautifully and lyrically is bringing us into a trance. And, and, and maybe if, if we can, we can share with our lovely listeners here of, of the actual concert in which we performed.

Leyla: Absolutely. That's a big part of this. We'll definitely have that footage on here so that we can see the choreography. Like you said, it's all tied hand in hand, the way you sing it the, the mode that you sing it in, right?

Fared: Yes. And, and the booklet itself here Kors Bake Board has done such a beautiful job with its graphics and I'm sure we can share elements of that so people can follow along, but.

Leyla: Definitely. I think one of the hallmark characteristics that I think I want people to walk away from is how musical Rumi is, right? And as you learn to memorize this poem, As you start to, to recite this yourself, and we'll have the audio of Fatty reciting this poem as well with the correct rhythm on, on the website, so you can listen to that over and over again as you learn it, it does put you into a trance as you're reading it, and you do get this sense of losing yourself as you're reading the poem, which is one of another one of the beauties of this poem.

Fared: And, and obviously today, I, you, you had said earlier that you were surprised when it fell into a six eight rhythm. I, I do wanna say that this can be expressed, for example, in a seven eight rhythm. It can be expressed in a four four rhythm. And, and we could probably talk about these various ways of how rhythm can change depending on how you read something. But yeah, the, I was excited about this because I do think that the repetition. The daugh daugh, this is a becoming is such an important concept in any language that you always learn the verb to be. And this is a really beautiful, beautiful example of taking that verb to be, to giving commands to another person and and using it to command someone to lose themself. What better command is there than that?

Leyla: Absolutely. So as always, we are going to continue the lessons on this poem. We're gonna go through it word by word, line by line. The more you understand the words and phrases in this poem, the more it will uncover itself to you. The more you recite it, the more it the meaning will uncover itself to you.

And as Fared started this tradition on this website Read this poem in a beautiful location, send it to us. And we have our videos of all of our students. And now we have this new community group where we have videos of all of our students reading these beautiful poems, which is very exciting. I'm definitely looking forward to that. Yeah. So Fared jan thank you so much for the first of our Radif retreat lessons and on our website. Every time that you see that Sitar symbol next to a lesson, you know that it's from, from the Radif retreat. Series that we're doing. So thank you so much Fared jan

Fared: Thank you. Thank you very much.